NOTE: Some of the following data can be also applied to the chapter “Transmission within herds”.

Epidemiology & pathogenesis of the PRRS virus

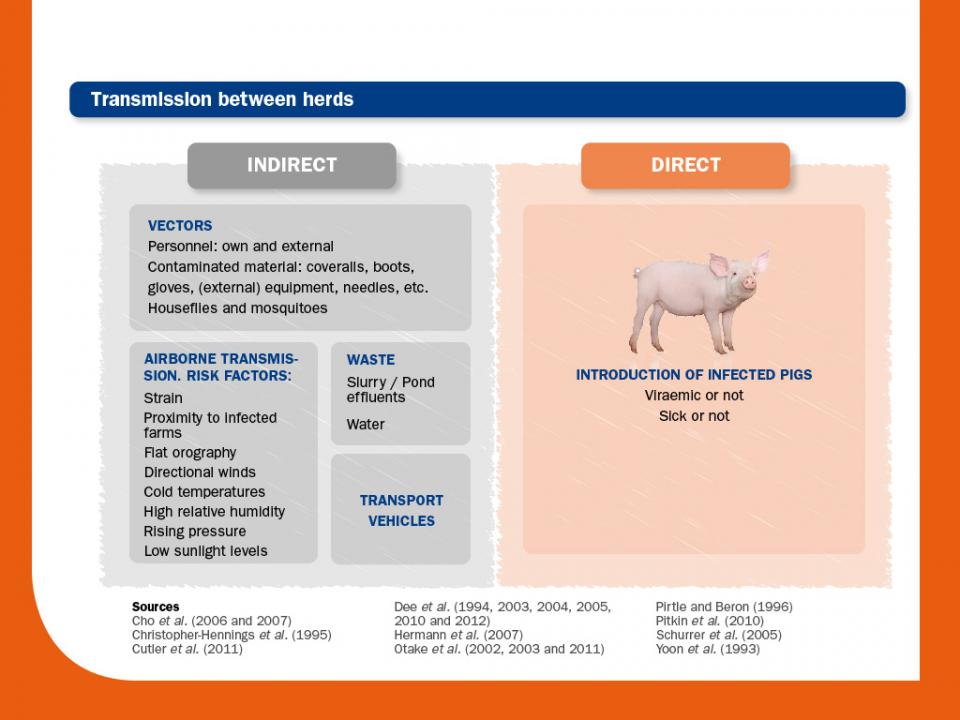

Transmission between herds

I. DIRECT TRANSMISSION:

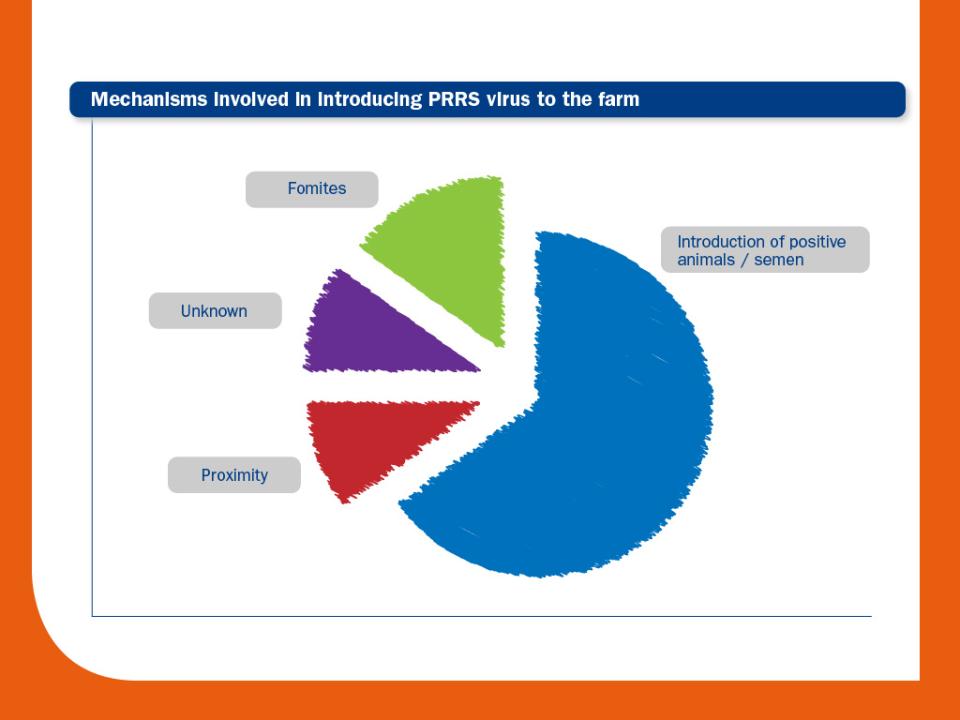

The most frequent routes of PRRS virus transmission between herds are the introduction of infected animals and the use of contaminated semen.

PRRS virus is spread mostly by semen and direct contact with infected animals. In the second case, the highest risk situations are introduction of positive replacements in reproductive herds, or introduction of weaned piglets from different sources (positive and negative) in fattening units. Regarding replacements, besides being a very important source of virus introduction, particularly when they are from an external herd with an unknown or positive PRRS virus status, negative gilts also have a significant role in the circulation of the virus when introduced on a positive/unstable farm; in this last case, they act as a constant flow of susceptible animals, which contributes to the infection being sustained.

Regarding transmission by other species, feral swine can act as a source of the virus, whereas many other species, including dogs, cats, raccoons, rats, mice, etc. are not susceptible to infection.

For more information about the role of semen and direct contact in PRRS virus transmission, please see the section “Transmission between animals”.

II. INDIRECT TRANSMISSION:

As detailed in the section, “Physical and chemical characteristics of PRRS virus”, the virus is fairly labile in the environment. It is important to point out that the virus does not persist in the environment or survive on fomites under dry conditions, and that cold temperatures favour its survival.

Nevertheless, indirect transmission of PRRS virus has been demonstrated by several routes.

a. VECTORS:

- Insects and rodents: Experimentally, mechanical transmission of PRRS virus has been demonstrated via houseflies and mosquitoes. The virus can survive for a short period on the exterior surface of the insects and in the gastrointestinal tract being the main site of retention of the virus. Some authors suggest that they may be capable of transporting PRRS virus at least 2.4 km from an infected farm. Regarding rodents, all available data indicate that rats and mice are not a reservoir for the disease.

- Personnel: Hands, coveralls, gloves, boots, etc. of personnel (own and external) can serve as mechanical vectors.

- Fomites: A number of contaminated fomites can act as mechanical vectors. Examples include any farm supply, external equipment (from electricians, plumbers, carpenters, etc.), needles, etc. It is also worth mentioning the importance of transport vehicles. It has been demonstrated that pigs can be infected through contact with the interior of transport contaminated with PRRS virus. The best solution for eliminating the virus from transport vehicles is washing, disinfecting (peroxygens and glutaraldehyde-quaternary ammonium chloride combinations for two hours are highly effective) and drying.

b. CONTACT WITH CONTAMINATED RESIDUES AND MEAT:

In lagoon effluents the virus can survive and can remain infectious for up to three or eight days at 20ºC and 4ºC respectively. Consequently, the recycling of lagoon water must be considered as a high risk practice. Also, PRRS virus can survive in water for more than one week. Therefore, it is very important to completely dry all surfaces (equipment, facilities, transport vehicles, etc.) after washing and disinfecting. In pig meat, PRRS virus can be detected for at least one week at 4ºC and for months under frozen conditions (-20ºC); uncooked pig meat should not be allowed into the farm.

c. AIRBORN TRANSMISSION:

Some authors have claimed that long distances (more than 3 or even 9 km) airborne spread of PRRS virus is possible. However, airborne transmission cannot always be demonstrated. In some cases, airborne transmission of PRRS virus cannot be detected in pigs sharing the same air space (in the same unit). In other cases, it has been demonstrated only for short distances (a few meters). In some countries, it has been estimated that over 1 kilometre beyond the initial outbreak, the probability of becoming infected through area spread is extremely low. In conclusion, in given conditions, methods of indirect transmission such as vectors seem to be more important than airborne spread.

Nevertheless, airborne transmission over short or long distances appears to be isolate specific (it is probably more common with type II strains) and, among other factors, depends on meteorological conditions.

Risk factors for airborne transmission. Risk increases depending on:

- Strain: related to virulence, more common with type II.

- Orography: flat.

- Proximity to infected farms actively shedding virus via aerosols.

- Winds: directional winds from infected to uninfected farm of low velocity with intermittent gusts.

- Temperature: cold temperatures (<5 ºC) increase risk more than warm temperatures.

- Relative humidity: high relative humidity (>75 %) increases risk more than low relative humidity.

© Laboratorios Hipra, S.A. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this website or any of its contents may be reproduced, copied, modified or adapted, without the prior written consent of HIPRA.