2b. Clostridium novyi Review (part 2)

Diagnosis of C. novyi

Diagnosis of C. novyi in pigs is difficult, primarily due to the fact that in the majority of cases the animals are found dead and that the time between death and necropsy introduces the possibility of postmortem invasion.

Other causes of death have to be ruled out, but it must be suspected in a case of sudden death with the necropsy findings described above (García, 2013).

Necropsy value

For accurate diagnosis, it is essential to perform postmortem examination and collect samples as soon as possible after death.

Diagnosis of blackleg, malignant edema, and infections by C. novyi can be based upon clinical signs, gross and microscopic findings at necropsy (Figure 5), Gram and fluorescent antibody stains of direct smears, and bacteriologic culture.

Figure 5. The abdominal cavity of a mature gestating Iberian breed sow at necropsy with enlarged and dark liver. Source: Dr. Alfredo García Sánchez, Centro de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas de Extremadura (CICYTEX).

Colonies of C. novyi are beta hemolytic, circular, raised-to-convex, translucent, gray, and shiny, with a granular surface and erose-to-slightly scalloped margins (Figure 6).

Figure 6. C. novyi cultivated on anaerobic blood agar. Source: Dr. Roy Schultz, Iowa State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

Diagnostic techniques

The most useful direct and rapid differential assay for myonecrosis agents is the fluorescent antibody test. The test is performed either on smears taken directly from clinical material or on isolates.

The use of direct immunofluorescence using fluorescent antibodies on smears from the liver has been described as a highly sensitive diagnostic technique, even better than culturing; however, it must be borne in mind that the longer the time between death and necropsy of the affected animals, the greater the probability of false positives (García, 2013).

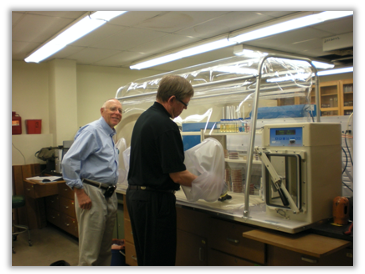

Clostridia are bacteria that are difficult to culture, because they are anaerobic, with C. novyi being the most complex of those commonly found in pigs (Figure 7).

In addition, sometimes merely isolating the clostridium species does not confirm the diagnosis, but its toxin also has to be detected as they inhabit the animal organism under normal conditions (García, 2013).

Figure 7. Cultivation of C. novyi in anaerobic chamber. Source: Dr. Roy Schultz, Iowa State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

On the other hand, use of PCR procedures may allow rapid identification of C. novyi and the implicated type (Poxton, 2007; Eklund et al, 1974).

In addition, enzyme immunoassay and toxin neutralization in CHO cells (Bormann and Schulze, 1999; Bormann et al, 2006) reveal alpha and beta toxins (Garcia et al, 2009), assuming that specific, toxin neutralizing antibodies are available as controls.

Control of C. novyi

How can we control C. novyi?

Death occurs suddenly in apparently healthy animals such that, because of the speed with which the disease develops, and especially because of the role played by toxins in its development, antibiotic treatment is ineffective (McKenzie, 2012); as is well known, antibiotics act against the pathogens and not against the toxins (García, 2013).

Viable attempts to control the disease in pigs have not been conducted, other than antimicrobial prophylaxis (Post and Songer, unpublished data, 1998–present). Some practitioners, however suggest prophylaxis with bacitracin methylene disalicylate (BMD) (Anonymous, 2007).

There are numerous reports in the scientific literature documenting the decrease in mortality in sows by means of the addition of bacitracin to the feed (García, 2013). Shultz (2001) observed a decrease of 16% when 250 g/ton of bacitracin methylene disalicylate was added to the diet during the last two weeks of gestation and until weaning.

There was also a decrease in piglet mortality and an increase in weight gain. Unfortunately in the European Union, there is currently a complete ban on the use of antibiotics as growth promoters (Regulation 1831/2003/EC on additives for use in animal nutrition).

Furthermore, the rapid elimination of carcasses by means of incineration or deep burial in lime is recommended, in order to reduce environmental contamination from the spores (García, 2013).

Vaccination

The brief clinical course of most histotoxic infections dictates prevention, rather than treatment, as a course of action. Commercial immunoprophylactic products usually consist of inactivated liquid cultures, eliciting antibody responses to bacterial surface antigens, toxic exoproducts, or both.

Immunization against C. novyi-induced infectious hepatitis is routinely practiced worldwide. This type of prevention is only feasible with the use of vaccines, generally toxoids or toxoids and second-generation vaccines based on native alpha or beta or recombinant toxins (García, 2013).

All around the world, vaccines are sold which contain the alpha toxoid of C. novyi for administration to breeding and adult sows. The manufacturers recommend a primary vaccination between 50 and 60 days antepartum and revaccination of the animals 25-30 days antepartum, with a single administration 30 days antepartum in subsequent gestations.

In outbreaks of sudden death, all the animals should be vaccinated (during gestation and lactation) with revaccination 4 weeks later (García, 2013).

Based upon these findings, it seems likely that appropriately structured immunoprophylaxis may be the answer for managing the disease in swine. We would expect this disease to follow the precedent of other clostridial diseases, in which solid immunity is achieved by toxoid components in a combined clostridial toxoid.